By

DECLAN BURROWES

Sometime in the 4th century, Emperor Constantine the Great put quill to papyrus in what would become one of history’s greatest acts of generosity. In gratitude to a pope who converted him to Christianity and cured him of leprosy, Constantine signed away vast tracts of the Western Roman Empire—including Italy, Greece and North Africa—to the Catholic Church.

Except he didn’t. This document, the so-called “Donation of Constantine”, was a total forgery manufactured by the Church in the 8th century and used for 700 years to justify papal supremacy over European kings and emperors. The Donation was, in two words, “fake news”.

Since humans have had written language, mendacious and mischievous actors have spread fake news to discredit, confuse, mislead, frustrate and profit. In the modern era, fake news largely inhabits the internet. You’ve probably seen most of it in the form of “clickbait” at the bottom of reputable news stories, where con artists promise some outrageous celebrity gossip or a shortcut to six-pack abs that a secret cabal of personal trainers is desperately trying to suppress.

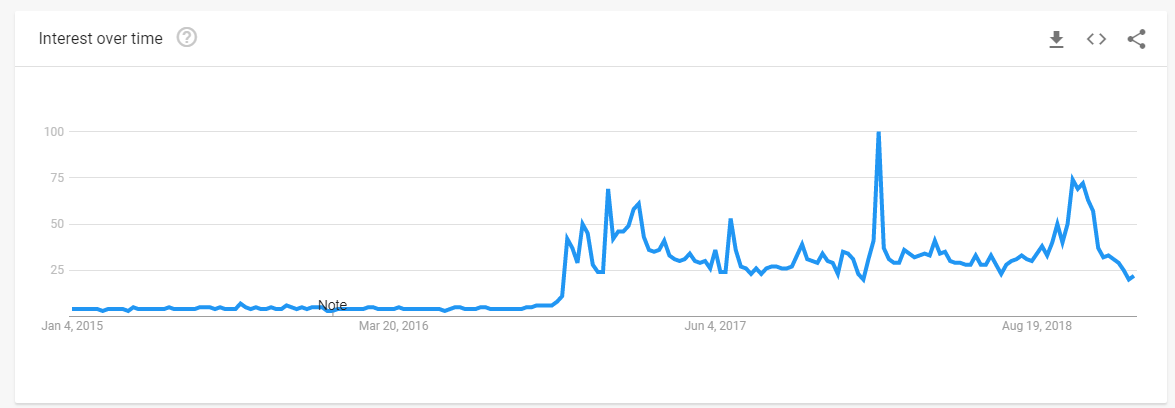

Despite the centuries-long presence of fake news in our everyday lives, there’s a good chance you hadn’t heard the term until November 2016, the month of Donald Trump’s surprise election win. In the immediate aftermath, many US media outlets claimed that fake news—particularly false, anti-Clinton stories—had played a major role in swaying voter sentiment towards Trump. Within a few weeks of his election, the President had appropriated the term for himself and turned it into an international catchphrase.

A post-2016 world

Since that fateful month, virtually every contentious, doubtful and disagreeable topic or opinion, from an Irish Ferries dispute to Satan’s temptation of Eve in the Garden of Eden, has been tarred with the fake news brush. And with good reason: gullible citizens, we are told, are at risk of being led astray by spurious stories planted by nefarious politicians, scammers and foreign governments. We should be afraid. Civilisational collapse and planetary disintegration might soon follow.

But are we really living through an epidemic of fake news? Have we truly crossed over into a shadowy “post-truth” world where up is down and left is right? Are we all unwitting players in a clandestine information war between global powers and secret interest groups? The data say no.

Research shows that during the 2016 US election, only a minority of people engaged with fake news. 8.5% shared fake news links on Facebook, according to New York University and Princeton, while the National Bureau of Economic Research claims that the average American adult read and remembered one fake news article. Old age was the single most important factor determining fake news consumption during the campaign. Those over 65 were seven times more likely than 18–29-year-olds to share fake news on Facebook, regardless of their political leanings.

But even among those who do consume fake news, it is impossible to measure a causal relationship between simply reading and sharing a story and subsequently voting in a particular way. Considering most fake news websites are hyper-partisan and visited by hyper-partisan readers, the worst effect a fake story is likely to have is to strengthen already firmly held beliefs. The pervasive idea that these websites are primed and ready to hypnotise and brainwash legions of innocent, unsuspecting moderates is, frankly, hysterical.

Mexican standoff

Unfortunately, none of that really matters. The cat is out of the bag. While we might not live in a post-truth world, we do live in a “post-2016” one. As public discourse has deteriorated and polarised, politicians, journalists, public figures and social media commentators have accusations of fake news unholstered and ready to fire from the hip. Fake news no longer means news that is false; it is news that we don’t like.

Indeed, fake news neuroticism has reached such a febrile temperature that all of us—businesses, the media, and private citizens—could be sleepwalking towards danger. French President Emmanuel Macron called for a legislative crackdown on fake news that skirts close to state censorship. Fianna Fáil’s James Lawless proposed prison sentences for anyone guilty of “spreading fake news”. Facebook has established an “election integrity centre” in Dublin, while Twitter and Google have all promised new technology-driven solutions to safeguard search results and newsfeeds. WhatsApp, to stop fake news stories going viral, has now even restricted the number of times a message can be forwarded.

Some of these proposals—particularly those aimed at decreasing the visibility of blatantly fake news—probably have value. Others—like kneejerk threats of incarceration—are tactless in an already heated and politically charged environment. We need to take a step back from the precipice and take a deep breath. Fake news is real. It can be an issue, but it does not represent an existential threat to the fabric of Western democracy.

Rather than fines, jail time and bans, decision-makers in Leinster House and Silicon Valley should be applying a soft touch and focusing on education.

Let’s start by teaching children critical thinking. The meticulous scrutiny of everything that sounds too good to be true should be our default setting—this isn’t just useful for spotting fake news, it’s an essential life skill.

Senior citizens, too, are prime targets for digital education campaigns. These don’t have to be expensive state undertakings; younger internet users can start the process by sitting down with their older relatives and talking them through the nuances and pitfalls of social media and web browsing.

Ultimately, it is the individual’s responsibility to read and consider multiple sources of information and arrive at their own informed opinion. Dealing respectfully with people who refuse to step outside their ideological echo chamber, trying as that may be, is a small price to pay for living in and engaging with a free society.

DECLAN BURROWES

Declan is PR360’s Content and Editorial Manager. He helps clients say as much as possible in as few words as possible. He likes animated political discussions, medieval history, and heavy metal.