Given the implications of Covid on the traditional procedures of electioneering, the Dublin Bay South (DBS) by-election campaign has been a challenge to the candidates’ normal state of affairs.

Shaking hands with the electorate, kissing babies, and entertaining constituents are, for now, a thing of the past as public health guidelines prevent candidates from close-quarters engagements.

The most significant difference has been increased reliance on social media, which has dominated each candidate’s communications strategy.

Outside of door-to-door campaigning, it has been difficult for some candidates to transition their electioneering to digital. Not everyone is naturally gifted at communicating their policies or even their own personalities online.

Usually, the digital learning curve is gentle. Candidates and their parties prepare their content and, before posting, test it among their campaign group, or, if they have the finances, their focus group. Policy is tweaked for clarity and to reflect the needs of the voters, within reason and feasibility.

But Covid has expedited this transition, leaving some in this race vulnerable to the many pitfalls of social media and digital technology.

The promises and pitfalls of digital technology

Many a politician has won or lost votes on the back of a single tweet. A great example of social media working for and against a candidate is Donald Trump during his re-election campaign, or in Ireland, the likes of Brian Stanley TD, Senator Lorraine Clifford Lee, and many others.

Best-practice social media strategy hinges on a targeted message, something that resonates with the audience you want to take action. The DBS candidates have depended on their social media to build their profiles, put forward policies, and interact with the local issues when they previously would have relied on face-to-face meetings.

In the process of building her profile, Fianna Fáil DBS candidate Cllr Deirdre Conroy faced tough criticism for her tongue-in-cheek videos, like the ‘Story of Deirdre’ video. The point of the video is unclear. If it was to create controversy or a story, she succeeded. However, if the aim was to outline her party’s policies, then we were left none the wiser.

If we compare campaigns, Labour’s Ivana Bacik used her social platform to highlight local concerns among parents seeking ASD (autism spectrum disorder) units in schools within DBS. While constituent clinics have been closed, she has connected directly with DBS constituents on a specific, important issue.

Engaging community groups and activists online can help demonstrate a candidate’s willingness to work on their constituents’ behalf. As social media also gives these groups a platform, they can access candidates and challenge them directly on the issues.

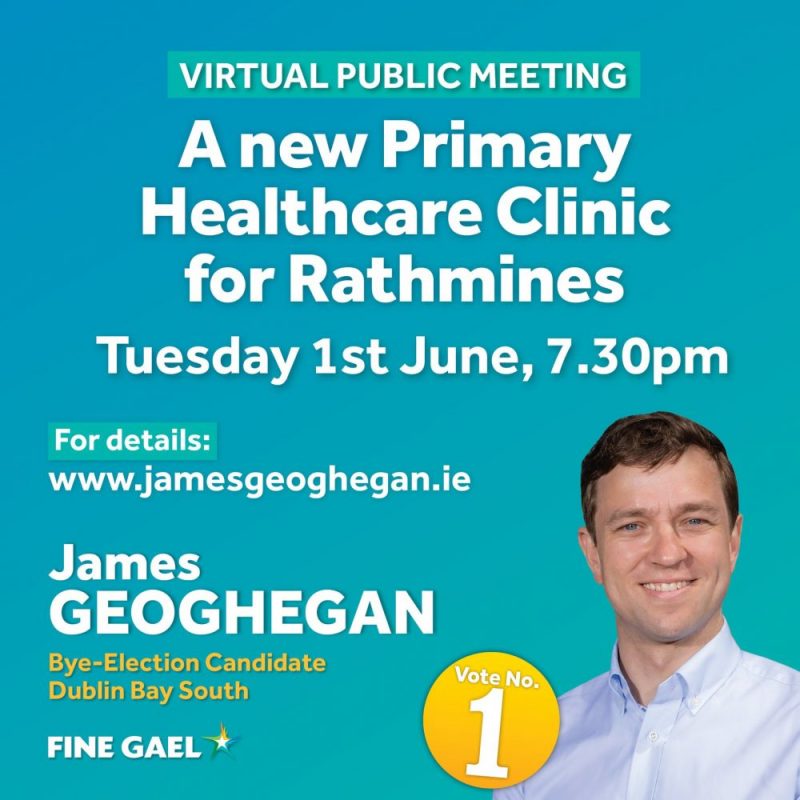

Zoom and other video chat platforms allow candidates to converse with a wider cohort of potential voters, as Cllr James Geoghegan did in his pursuit of healthcare facilities for DBS.

Gary Gannon, the sitting Dublin Central TD, has used Zoom to great advantage by hosting constituency clinics with multiple constituents per meeting, engaging with issues in his direct remit as education spokesperson.

Saying the right thing—and looking good too

As social media in politics becomes more important, so too do the rules of engagement. Politicians and parties have to be on the ‘right’ side of the conversation or be ready to face into a barrage of criticism. They must straddle their own political ideologies while also augmenting their views to suit popular policies that reflect their electorate’s views.

An interesting development has been the use of targeted ads on social media. Parties have been exploring the use of demographic-specific ads. Sinn Féin, for example, directed its housing policy straight to the newsfeeds of 18–35-year-olds during the 2020 general election.

But targeting alone is not enough. Cutting through busy newsfeeds requires authentic, personable communications and strong visuals. Social media, particularly platforms like Instagram and TikTok, gives candidates a space to be creative in the ways that old, tired party literature doesn’t. It allows them to demonstrate their personality to a greater audience, which is key to generating empathy.

It is this ability to endear empathy—and just plain likeability—that is more often the key to success at the ballot box than lofty policy goals. While voters have major concerns about policy issues, they have to feel a connection with a candidate to be able to buy what they are selling when it comes to solutions.

The use of visuals has been particularly interesting in the DBS by-election. Many candidates like Brigid Purcell, Sarah Durcan, and Ivana Bacik have utilised creative, eye-catching imagery in their campaign posters and social media profile pictures to capture their more down-to-earth side.

Surviving in the digital arena

For politicians, social media has plenty of pitfalls. It’s not always possible to make and drive the narrative, even with a tried-and-tested electioneering formula. Uncomfortable or controversial issues that once might have fizzled out after a few days in the papers can’t be escaped online.

This has been particularly true for Fine Gael and its DBS candidate Cllr Geoghegan on the issue of gender representation; among the major parties, he is the only male candidate in the field.

Geoghegan, as the frontrunner, has had to face criticism from women on social media concerned about the lack of female representation in the constituency (and nationally) and his ability to adequately represent female constituents on female issues.

Parties and candidates need to prepare for these scenarios. Good communications include knowing when to engage and when to disengage. In a long game like politics, you don’t want to get bogged down in the short game of arguing your position haphazardly on Twitter.

Regardless, social and digital media are now part and parcel of contemporary electioneering. If politicians don’t engage with social media, they are cutting off an arm in the communications battle that is politics.

By engaging different social media channels intelligently and developing authentic, targeted content, politicians widen their audience and can quickly and more efficiently broadcast their message.

As people strive for connection in a less connected world, social media allows both the constituent and the politician to interact more frequently, more easily, and in greater numbers. Politicians considering a run for the next general election must prioritise the development of a robust social and digital strategy.