After years of uncomfortable government scrutiny, outrageous clashes with a sitting US president, and difficult philosophical soul-searching on the nature (and potential boundaries) of free speech, Twitter is trialling a new community moderation feature, Birdwatch, that gives users the power to flag and contextualise potentially misleading content.

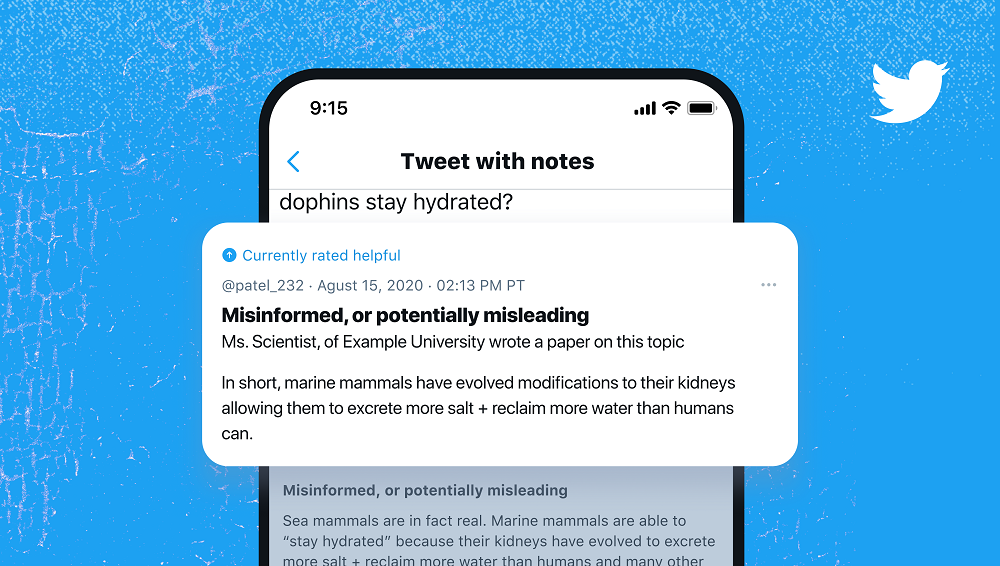

With Birdwatch, which is currently in closed beta on a standalone site, pilot users can asterisk contentious tweets by submitting clarifying “notes” and rating the “helpfulness” of notes left by others. Twitter claims that once there is “consensus from a broad and diverse set of contributors”, community-written notes will eventually be visible to the public directly on tweets.

All this data will be downloadable. Furthermore, as the Birdwatch algorithm is developed, Twitter “aims” to publish the code, so theoretically anyone will be able to investigate allegations of bias or tampering.

At surface level, Twitter’s attempt at creating a less monolithic and more transparent way of moderating content appears useful and progressive. While the real-world repercussions of fake news may be overstated, it is self-evident that in a time where mass communications can be carried out virtually instantaneously, without a sense-checking “authority” or, at the very least, a “are you really sure you want to post this?” button, there is always potential for misunderstanding, obfuscation, and even worse.

But making Birdwatch work won’t be easy, and there is still much that we don’t know about how it will ultimately function. For example, how much content moderating power will Twitter be ceding to its community? How much will it retain, and will it be able to intervene in Birdwatch disputes at its own discretion? Once the closed beta test is over, will anyone be able to become a Birdwatcher?

How these questions are answered will determine whether the tool will work as intended—fairly and transparently—or function simply as a pragmatic power transfer from an embattled Silicon Valley to a zealous neighbourhood watch.

Birds of a feather

Following Birdwatch’s announcement last week, one Forbes writer described it as a “Wikipedia-style approach” to the fight against misinformation, referencing that site’s (frequently criticised) reliance on community volunteers to write, edit, and factcheck articles.

But what the writer failed to mention is that Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales actually did attempt his very own “Wikipedia for journalism” in 2017. WikiTribune retained a small team of professional journalists who wrote articles that were then factchecked, edited, and updated in real time by community volunteers. The site was, in Wales’s own words, a fix for “broken journalism” that would, through a combination of journalistic expertise and constant community dialogue, get to the essential, immutable truth of a story.

WikiTribune never really took off and petered out completely a year later. Part of the problem was that only an extremely small number of time-rich WikiTribune evangelists, who had their own narrow interests, were ever willing to put the effort into factchecking and editing. This influential minority allegedly caused editorial issues; the UK Times suggested that the site, ironically, was itself biased on certain topics.

This may be a problem for Twitter too. In his announcement blogpost, VP of Product Keith Coleman acknowledged that ensuring Birdwatch “isn’t dominated by a simple majority or biased by its distribution of contributors” will be difficult, even “messy”.

The way in which social networks are structured and grow means that isolated “bubbles”, which are typically impervious to different opinions and viewpoints, are common and perhaps inevitable.

In Twitter’s case, 60% of adult users in the US identify as a Democrat or lean Democrat (compared to 52% of the US general population), but just 35% identify as Republican or lean Republican (compared to 43% of the general population). Furthermore, 92% of all tweets posted by US users between November 2019 and September 2020 were posted by just 10% of users.

In isolation these aren’t problems per se, but if Twitter wants to avoid WikiTribune’s fate, it will have to carefully consider how to avoid content moderation power permanently, and unfairly, coalescing in the hands of the top 10%.

Who watches the Birdwatchers?

Twitter’s traditional top-down, opaque moderation policies have long attracted the ire of journalists, activists, and celebrities. To some, the site is too hands on; to others, too hands off. Facebook, YouTube, and others have struggled similarly. Where is the harmonious middle point, where civil free debate is cherished and abuse clearly defined and demarcated? Some have tried to find it, while others have veered away towards the extremes.

A laissez-faire, quasi-libertarian approach is what alternative microblogging site Parler ostensibly attempted in 2018, yet it quickly turned into a Wild West echo chamber for conservative personalities banned from Twitter. It rose to infamy last month when it transpired that it had failed to moderate certain users mobilising for the riot at the US Capitol.

Twitter’s stance has hardened considerably over time, particularly since 2016, and not without confusing many of its users in the process. What qualifies as acceptable content has changed, changed back, changed again, and been generally poorly communicated. This has led to mystifying, even mysterious, deletions, suspensions, and reinstatements, which in turn have led to repeated accusations of bias and even active censorship.

Consider, for example, the contrast between feminist writer Meghan Murphy, whose account was permanently banned after she misgendered a transgender person, and former Malaysian prime minister Mahathir Mohamed, whose tweet explicitly justifying the killing of “millions of French people” was initially left up with a disclaimer and then removed after protest from a French minister.

While Birdwatch might not put an end to Twitter’s often confusing and cack-handed attempts at moderation, transparent discussion between users may at the very least help to explain the rationale that determines which content is flagged or deleted. Whether that rationale will be acceptable to offending tweeters is another matter entirely.

From code to quill

Social networks, whether they like it or not, have become content publishers. They give billions the means to project opinions and influence other people, frequently at uncontrollable speeds. One only has to look at the ongoing GameStop saga to see how discussion in an obscure Reddit forum led to Wall Street panic and White House consternation in less than two weeks.

It is hardly surprising, then, that many politicians, including Irish TDs, have reacted by calling for all manner of state interventions into internet affairs, including public oversight of social networks, fines for platforms that are slow to take down illegal or offensive content, and even the dismantling of larger conglomerates like Facebook.

If Twitter does indeed seek to evade the eye of Sauron, then the creation of Birdwatch may be more shrewd move than benevolent crusade against fake news. By ceding degrees of content moderation to the userbase in a transparent or otherwise “fair” way, Twitter might be able to avoid continuous accusations of incompetence, uncomfortable parliamentary inquisitions, and hefty fines. It is, after all, far harder to fault a million earnest users than a single billionaire tech CEO.

For now, though, Jack Dorsey et al have their work cut out communicating, clarifying, and implementing their new technology. Their users will determine the practicality and success of Birdwatch, and with it, Twitter’s freedom to conduct business as usual.

About the author

Declan is 360’s primary content creator, responsible for strategising, managing, and writing editorial campaigns for our client portfolio. He ghostwrites opinion editorials for C-level leadership and edits and publishes 360’s Full Circle magazine. Previously, Declan freelanced as a journalist and voiceover.